Posted by: Chad M. Gesser

Twitter: @profgesser

Email: chad.gesser@kctcs.edu

Each semester I cover different aspects of deviance and crime with my Sociology students, and I’m always intrigued to hear their varying perceptions of crime and violence in our community, the nation, and the world.

It is inevitable that the prevailing viewpoint is that we do indeed live in a violent society. In discussions this week, I had one particular student who is married to a local police officer share that her husband refuses to allow her to walk, jog, or run alone at night in her neighborhood and community for fear of violence. An argument can be made that he is just being safe, but it certainly does beckon the question: How safe is my community? My country? Society in general?

Ten years ago Barry Glassner released his “Culture of Fear“, which examined how various social forces from media to the government influence Americans’ perceptions of safety and violence in the United States. Glassner has since updated his book, continuing to provide documentation and evidence that the culture of fear we live in is largely unjustified. In most places in the United States, and yes there are exceptions, but in most places in the United States, a fear of violence and crime is largely unfounded. This fear rests in an inaccurate assessment based on opinion, largely influenced by the mass media.

Let’s examine a couple examples that influence our culture of fear. The image at the beginning of this post is the threat level diagram that was implemented by the United States Department of Homeland Security following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The system was designed “create a common vocabulary, context, and structure for an ongoing national discussion about the nature of the threats that confront the homeland and the appropriate measures that should be taken in response. It seeks to inform and facilitate decisions appropriate to different levels of government and to private citizens at home and at work.” (Source link) During 2002-2004, anxiety rippled through the U.S. population as the threat levels fluctuated from blue to orange. In late 2009, Wired magazine reported proposed changes to the threat level system, given the lack of public confidence in the system and the suspicious nature and use of the system for political maneuvering.

Various organizations (academic and government) monitor the types and degree of crime committed all across the United States to determine the extent of violence and safety to the population. Historically, serious crimes have been monitored to get an accurate assessment to the degree of violence and crime occurring in the United States. Serious crimes that are monitored are homicide, aggravated assault, robbery, and rape.

The data above from the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics shows both the recorded rate of violent crime and the rate of victimization reported to the police. These two measures combined give us a very good assessment to the extent that violent behavior and crime are occurring in the U.S. Given the recent history of the war on terrorism and terrorism in the United States, perhaps American society is doomed to be scared out of it’s wits for some time to come. However, the fact of the matter is that total violent crime in the United States is lower now than it has been in over 35 years.

A closer look at the victimization rate shows us the changes by age group over time.

This data further verifies that few people are being victimized by violent behavior and crime.

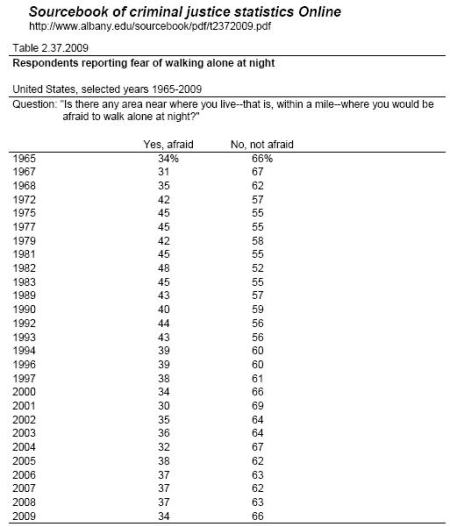

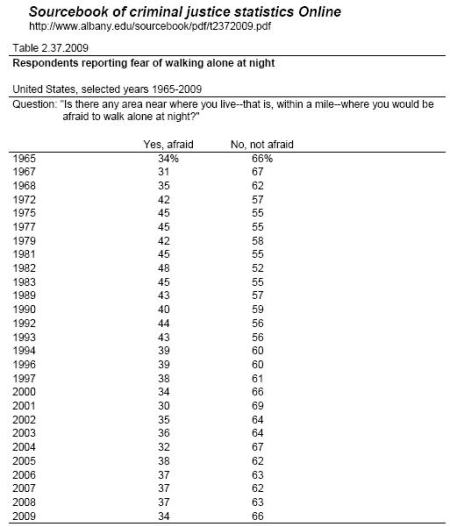

While most people indeed are not afraid of walking alone at night, data from the Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics documents that the fear, while changing somewhat over time, has not changed over the past 45 years.

How else does our society nurture and foster a culture of fear? Do you feel safe in your neighborhood, your community? Why is feeling of safety important? How does a one’s perception of fear and violence affect one’s outlook on life? How does it affect how you might interact with strangers?

nd home to approximately 15,000 people. But Cabrini Green wasn’t an ordinary apartment complex; to many, it represented everything that was wrong with public housing in American cities. Cabrini Green was the scene of countless acts of violence over the course of its decades as a predominantly poor, predominantly African American public housing complex. Cabrini Green stood until last month, when the last of the high rise building was demolished. During that time, Cabrini stood not just as public housing, but as a symbol of the problems of public housing in America’s cities.

nd home to approximately 15,000 people. But Cabrini Green wasn’t an ordinary apartment complex; to many, it represented everything that was wrong with public housing in American cities. Cabrini Green was the scene of countless acts of violence over the course of its decades as a predominantly poor, predominantly African American public housing complex. Cabrini Green stood until last month, when the last of the high rise building was demolished. During that time, Cabrini stood not just as public housing, but as a symbol of the problems of public housing in America’s cities.

One of the characteristics of society is a stable pattern of behavior over a long period of time in one geographic place. Some sociologists suggest that people behave the same under similar conditions because they follow a shared set of social rules for behavior. These rules can grouped into categories such as values, norms, folkways, mores, and laws. Continuing down this line of thought, you might suggest that you can teach people the rules, but not everyone will obey them! Society, however, reinforces its rules through social sanctions.

One of the characteristics of society is a stable pattern of behavior over a long period of time in one geographic place. Some sociologists suggest that people behave the same under similar conditions because they follow a shared set of social rules for behavior. These rules can grouped into categories such as values, norms, folkways, mores, and laws. Continuing down this line of thought, you might suggest that you can teach people the rules, but not everyone will obey them! Society, however, reinforces its rules through social sanctions.